“I’m sorry. I just don’t like the sound of it!”

My mother at breakfast in 1953, in the kitchen of our one-bedroom home in Vancouver. We lived a few blocks east of Little Italy, a quaint area in the city. We kids loved to walk the 2nd Avenue hill and trudge up the other side to Copp’s Shoes, which offered the most wonderful toffee suckers wrapped in wax paper if you bought any small thing – even a pair of shoelaces. What a thrill to open the wrapper and taste that creamy caramel toffee inside!

At the moment, however, toffee suckers were off the table, as it were, since my father had just proposed that we pick up and move from Vancouver, lock, stock and barrel, to a remote logging camp on Vancouver Island. Hence, my mother’s reaction.

At the time, our tiny, stucco house felt cramped and old. Cold, too, as I recall, since it rained steadily in Vancouver and my parents had to economize on heat. However, Granny Davis, who lived in our basement suite, owned a pot-bellied stove. Her place always exuded a cozy warmth. Orange poppies bordered the cement stairs down to her door, and I remember smelling their pungent odour when we visited her for tea and cookies on occasion.

My folks were young then, children of the Great Depression, struggling to raise two kids and earn enough money to keep a roof over our heads. Times had to be tough for my mother to even consider such a drastic step as my father was proposing. The Post-War boom hadn’t yet reached full momentum, so many families still struggled as we did. Luckily, Mom had attended university on scholarships and now had a full-time teaching job in an elementary school.

Looking back at their discussion, I picture my father reaching for the sugar and stirring two lumps into his coffee, then sucking on a third in the Scandinavian way. He likely wore his Yellow Cab hat, one that he no doubt hoped to “deep six” for a teacher’s garb if he could convince my mother that this move was a good thing.

“It’s a principalship in the Nimpkish Valley!” he exclaimed. “And it’s a two-room school, so you and I would be the only teachers. We’d have free reign!”

He made it sound promising, even exciting.

“Why would you be the principal when it’s your first appointment?” objected my mother. “I’m the one with the teaching experience! You’ve only just earned your diploma.”

“I agree it’s not fair, but you know how the world works, sweetie,” replied Dad. “They always offer the men the best jobs. At least the money will be all in the family. And it’s an adventure! Think of it that way. Remember, Huey Grayson will be there.”

“Your forestry friend?”

“That’s the one. He’s stationed at Woss Camp, where we’d be living. So we’ll know someone going in.”

“Yes, I remember him. He has the thickest British accent I’ve ever heard,” said Mom.

“Well, knowledge of the Queen’s English is no barrier to a love of virgin forest. He knows they could log that area for decades and hardly make a dent.”

I can certainly understand my mother’s reluctance to move. There she sat, staring at one dependent child across the kitchen table, while offering strips of toast to a smaller child on the floor beside her. It was difficult enough to be a working mother in the city. What would it be like juggling work and family in a remote logging camp?

“Who’ll look after the kids during the day?”

“We’ll find somebody. We’ll hire a nanny before we go.”

That sounded reasonable, but I’m sure that even my father, who had grown up in mining camps as a child, didn’t fully grasp how rustic those Island logging camps really were.

“There aren’t any roads!” bemoaned Mother. “How will we get in and out?”

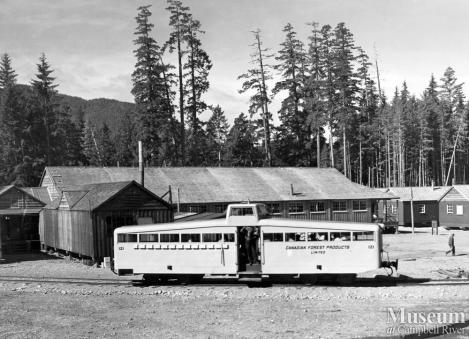

“We’ll go by steamship from Vancouver,” said my father. “Then they have company rail cars from Englewood to the logging camps. They call them speeders.”

“Speeders!? Good grief. I’ve seen pictures of those things,” said Mom. “They look like big tin lozenges on rail wheels. Are they safe?”

“They’re safe,” said Dad. “Not exactly luxury travel, but they have bench seating around the walls and sliding doors to get in and out. Like self-propelled boxcars, really. And it’s only a two-hour ride!”

It was true. You could only get halfway to the logging camps by steamship or by sea plane. Then you took a long railway ride in those metal contraptions, not well-equipped for passengers. And CANFOR, Canadian Forest Products, owned it all. Or leased it, which amounted to the same thing. They owned the camps, the houses in the camps, the rail line, the speeders. And for a song, they held long leases on the forests, courtesy of the BC government.

“It’s a booming frontier!” said Dad. “They’re making nothing but money logging those mountains, so everyone who works for them does pretty well.”

Then he quickly changed the subject.

“Would you like to go on a big ship, kids?” he said, glossing over the rail car part. Naturally, our young eyes lit up. Then he sweetened the deal. “And sleep in a stateroom for a whole night?”

We were sold. Or at least, I was. My mother still frowned. She did not like that our ship would dock at a remote log dump, and that when we arrived there, we’d still be in transit. She knew that Englewood existed only to receive logs from down-Island, logs which were then dumped into Queen Charlotte Strait, tied into log booms, and towed to sawmills and pulp mills in Vancouver, Prince Rupert or Victoria. Our steamship port wasn’t much more than a huge pier, cut out of the wilderness. There was no guest house.

My mother had one final protest.

“What if one of us gets sick?”

“No problem! There’s a camp medic, and they can always fly us out to Alert Bay if they have to. It’s only a twenty-minute flight by emergency float plane.”

“Twenty minutes! We could bleed to death in that time!”

As it turned out, some bleeding did take place during our stay there, and one of us did fly out on that emergency float plane.

I’ll tell you more about that when we get there.